Publisher:

blogs.lse.ac.uk

Now available at:

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/book-review-twilight-of-impunity-the-war-crimes-trial-of-slobodan-milosevic/

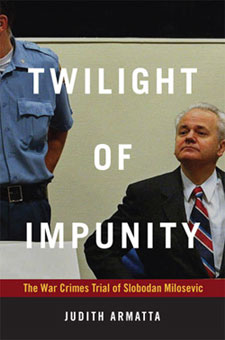

Book Review: Twilight of Impunity:

The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic

Reviewer:

Ramona Wadi

Dec 11 2011

A vital read for students and researchers interested in the ramifications and

contradictions of international law and justice, Ramona Wadi finds that Judith Armatta's detailed

narration and analysis of Milosevic's trial an important contribution to the field.

A vital read for students and researchers interested in the ramifications and

contradictions of international law and justice, Ramona Wadi finds that Judith Armatta's detailed

narration and analysis of Milosevic's trial an important contribution to the field.

by Judith Armatta

Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic.

Duke University Press

2010

In a narration which deals with the responsibility of establishing guilt 'beyond a reasonable

doubt' within an international law framework, Judith Armatta's detailed account of Slobodan

Milosevic's trial delves into legal ramifications, personality portrayal and

testimonies, whilst exhibiting an awareness of split memory consciousness

beyond the realm of legality and justice.

Butcher of the Balkans or martyr of nationalism, Slobodan Milosevic was the first leader to

be internationally indicted for crimes against humanity. In a trial lasting

466 days in

the span of four years, three indictments were brought against Milosevic – crimes against

humanity committed in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo. The Kosovo indictment charged Milosevic with

international law violation including deportation, forcible transfer, murder and persecution.

The Bosnia and Croatia indictments carried charges of genocide, complicity in genocide and

Geneva Convention violations.

466 days in

the span of four years, three indictments were brought against Milosevic – crimes against

humanity committed in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo. The Kosovo indictment charged Milosevic with

international law violation including deportation, forcible transfer, murder and persecution.

The Bosnia and Croatia indictments carried charges of genocide, complicity in genocide and

Geneva Convention violations.

The trial was replete with contrasts – in attitude, temperament and legalities. Commencing

with the prosecutor's declaration that '… no one is above the law or beyond the reach of

international justice', the declaration was immediately rebutted by Milosevic's

allusions to the concept of freedom, 'I, arrested, imprisoned, am nevertheless

the free' and his contempt of international law, as he stated 'I challenge the very

legality of this tribunal'. With a defiant attitude coupled with self-representation,

Milosevic regaled the world with an insight into his construction of history.

Whether it was an attitude of detachment from, or denial of reality, Milosevic's dismissal

of atrocities jarred with the testimonies of survivors. Witnesses who survived the

concentration camps recounted severe torture of the most extreme kind. These witness

accounts were refuted by Milosevic, whose rhetoric countered that people were

incapable of committing such evil extremes, thus detaching himself from the

responsibility of the massacres.

With evidence accumulating against Milosevic, including the setting up of a Joint

Command in order to bypass soldiers opposed to military action, Milosevic's

self-defence remained chaotic; a leader facing a hostile international community,

at times portraying himself a victim of international conspiracy, a persecuted

victim who in turn seized the opportunity to launch his own accusations against

the NATO intervention. Despite evidence purporting Milosevic's awareness of the

murder rampage through communication channels, the SDB and other special reports,

he continued to exhibit a detachment, claiming that his actions were classified

as anti-terrorist operations, that deaths were the result of collateral damage in

civil war, and at times his defence was to charge witnesses with conspiracy.

In several instances, Armatta remarks on the futility of holding NATO accountable

for any deaths during its campaign. The prosecution claimed not to have enough

evidence linking the people's displacement to NATO airstrikes. General Wesley

Clark was allowed to testify by the US, but only under condition that NATO would

not be included in the testimony. During Clark's testimony, the court adjourned

for a few minutes to receive a fax signed by Bill Clinton which read, ‘Contrary to

Mr Milosevic, General Wesley Clark carried out the policy of the NATO alliance to

stop massive ethnic cleansing in Kosovo with great skill, integrity and determination.'

The categorical denial of witnesses stating that NATO inflicted no damage on the villages

raised doubts of accountability; however the testimonies were not rendered invalid.

Milosevic's death on March 11, 2006 prompted allegations of foul play, fuelled partly

by a letter in which Milosevic alleged he was being poisoned. To counter the allegations,

an autopsy report later stated that he died of natural causes. Past documents were

also recalled, citing that since the commencement of the trial, Milosevic was said to

be at great risk of cardiac arrest. The abrupt halt to Milosevic's trial meant that

charges of genocide remained unproven due to the court's failure to establish the

commencement and perpetration of the Srebrenica genocidal campaign. The culpability

for genocide seems to have been resting on more Generals apart from Milosevic.

In the absence of a declaration of genocidal intent, circumstantial evidence

precludes a finding of genocide.

In the aftermath of Milosevic's demise, the concept of split memory consciousness manifested

itself in Serbs; with a minority of thousands hailing him as a martyr. The recollection of

Milosevic as a national hero prompted outrage from his opponents, who described the

homage as humiliating and tantamount to betrayal. The court's inability to establish

a widespread genocide failed to bring about closure to the survivors, in the

absence of a verdict and in acknowledging the imperfections of law and justice.

Also, the concept of establishing proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, as required by

international law, seems to have been flawed by NATO's assisted impunity with regard to

investigation for war crimes.

Armatta's detailed narration and analysis of Milosevic's trial makes this book vital for

students and researchers interested in the ramifications and contradictions of international

law and justice. There is clarity in her portrayal of inevitable flaws within

the legal system which rendered Milosevic's trial incomplete, allowing the reader to

analyse how the parameters within which 'no one is above the law' is rendered invalid,

namely the distance kept by the US in its dealings of with the ICTY and the dynamics

which enable NATO's war crimes to remain untarnished by any judicial procedures

Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic.

Duke University Press, 2010

Find this book:

Google Books

Amazon

This entry was posted in Global Politics, Ramona Wadi and tagged Geneva

Convention, genocide, human rights,

human rights abuse,

international relations,

justice, nationalism, NATO, Slobodan Milosevic, war.

Bookmark the permalink.

Web Editor Note:

Blog post review is also located at

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/40991/1/ (Acrobat format: PDF)

A vital read for students and researchers interested in the ramifications and

contradictions of international law and justice, Ramona Wadi finds that Judith Armatta's detailed

narration and analysis of Milosevic's trial an important contribution to the field.

A vital read for students and researchers interested in the ramifications and

contradictions of international law and justice, Ramona Wadi finds that Judith Armatta's detailed

narration and analysis of Milosevic's trial an important contribution to the field. 466 days in

the span of four years, three indictments were brought against Milosevic – crimes against

humanity committed in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo. The Kosovo indictment charged Milosevic with

international law violation including deportation, forcible transfer, murder and persecution.

The Bosnia and Croatia indictments carried charges of genocide, complicity in genocide and

Geneva Convention violations.

466 days in

the span of four years, three indictments were brought against Milosevic – crimes against

humanity committed in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo. The Kosovo indictment charged Milosevic with

international law violation including deportation, forcible transfer, murder and persecution.

The Bosnia and Croatia indictments carried charges of genocide, complicity in genocide and

Geneva Convention violations.